PSA test for prostate cancer screening: should he or shouldn’t he?

Even his doctor doesn’t know for sure.In some ways the news that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has stopped recommending routine prostate cancer screening through the mechanism of the PSA blood test mirrors the same group’s finding in 2009 that routine mammograms for women between 40-50 should no longer be suggested.

The problems the panel faces are very similar to those it was grappling with in the mammogram situation: a simple and relatively inexpensive screening test for a fairly common but extraordinarily nasty disease, confusing and difficult-to-evaluate statistics about whether or not the test really decreases mortality, and a treatment that has its own negatives in terms of pain and suffering (both physical and emotional). Now as then, the task force will be accused by some of cutting back on a benefit in order to save the money that would otherwise be spent to cover the test and its results. The doctors will be seen as hard-hearted and/or scientifically incompetent or simply wrong in their conclusions.

But although the two situations (mammograms and PSA tests) are somewhat similar they are not identical, with the mammogram decision actually being somewhat easier. As I wrote in November of 2009, when I disagreed somewhat with the panel’s recommendations:

The listed harms of extra mammograms seem minor although more frequent [than the harms of not doing them], the benefits admittedly less frequent but rather more major—life vs. death, for example. And deaths in the age group specified—women in their forties—involve a population of young mothers. We’re not talking about death squads for grandma here; we’re talking about mommy.

Answering Questions About the P.S.A. Test

Prostate cancer is a related but somewhat different disease with even more confusing demographics and more serious (and common) side effects of treatment, presenting doctors with a host of conundrums [emphasis mine]:

Prostate cancer is the second-leading cause of cancer death among men, after lung cancer. In 2009, it was diagnosed in approximately 192,000 men. A small number of tumors are very aggressive, but the majority of prostate tumors are not likely to cause death. They grow very slowly, and only a fraction break out of the prostate, seed new tumors in other parts of the body and kill the patient. The current thinking is that about 30 percent of men in their 40s have prostate cancer, 40 percent of men in their 50s and so on, right up to 70 percent of men in their 80s. Yet only 3 percent of all men die from the disease. In other words, far more men die with prostate cancer than from it, and only a tiny fraction of prostate cancers ever cause symptoms, much less death.

But here is the tricky part: Unless there are symptoms or a finding on a physical exam, doctors generally cannot accurately predict which cancers are destined to be indolent, to sit around for years growing slowly, if at all, and those that will ultimately prove lethal.

You can see the dilemma, and it’s far worse than that facing doctors advising women about mammograms, because breast cancer—although common—is both less frequent than prostate cancer and far more reliably lethal if left untreated. What’s more, the interventions for prostate cancer are especially troubling and common in their possible side effects:

About half of men who undergo radiation or surgery [for prostate cancer] will have permanent side effects like impotence and incontinence. Up to 1 in 200 men die within 30 days from complications related to the surgery.

Those who advocate routine screening say it’s worth it in lives saved. But opponents point to studies that show no difference in mortality between the screened and the unscreened.

Until we know more, the best solution is probably (as the article concludes) to inform men of the risks and benefits of screening before they take the PSA test and let them decide whether they want to roll those iffy dice. This follows a recent trend in medicine in which patients are more and more often being asked to take responsibility for decisions that used to be the province of doctors. This is either good or bad depending on how much you want to depend on your doctor.

[NOTE: And, of course, the entire issue has insurance consequences: will PSA tests now be removed from routine coverage?]

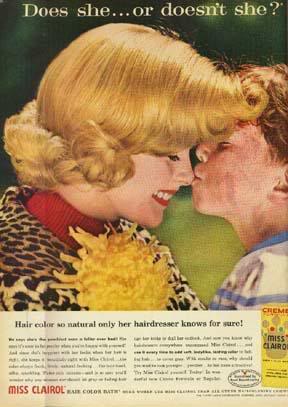

[ADDENDUM: On a lighter note, those of a certain age may get the reference in the title and first line of this post. But for the others, here's some help:

One of the most successful ad campaigns ever.]

No comments:

Post a Comment